Cartography: Forge

In the beginning, there was a single sniper rifle on Colossus. And it was not so good.

Forge began with the intention of empowering players with the ability to change the flow of the game. It ended up being the single most most important addition to Halo since online multiplayer.

My first impression stemmed more from the fact that it was a game mode, rather than an object editor, and how I hadn’t seen anything like it before. I try to evaluate things based on what they try to be, rather than what I wanted them to be, and on that basis, I thought the tool was ideal for what it was primarily designed for: spawn, weapon and objective placement, and a sandbox-y place to play with friends.

GhaleonEB

Forge wasn’t designed to be a map editor, at least not in the traditional sense. There was no terrain editing to be seen, no messing about with textures, lighting or most of what players have come to expect from a fully functioning editor. Forge was different, intentionally so. Forge would operate on top of the existing maps. It allowed players to place objects or relocate vehicles, weapons, spawn points and objective locations.

When Forge was revealed it was pitched to journalists as both an object layout editor and an exciting new type of multiplayer that could stand beside both Campaign and traditional multiplayer as a viable and independent game mode. Teams would engage in combat on a given level with the Monitors on each team helping to tip the balance of power towards their team’s favour. Whilst one Monitor would spawn a collection of vehicles for his own teammates, the rival monitor would be rushing to delete them before they could be boarded or rushing back to his own team to create some defences before they arrived. Monitors would assist their teams in new dynamic ways not possible in traditional multiplayer. It was going to be crazy and exciting but it just didn’t happen that way.

Whilst some players would take the time to use Forge to study the weapon and player spawn layouts of a given level, other players would throw tanks at each other. Some would attempt to alter the maps and improve upon their layouts whilst others would simply create the biggest explosion they could within the budget available. It seemed as if nobody was interested in forming teams and having serious, competitive multiplayer matches in Forge. It also turned out that the option to restrict editing didn’t actually work. Not many players cared. They didn’t care because they were busy creating their own fun in this new, exciting playground.

As players became familiar with Forge following Halo 3’s release, Bungie’s post release support engine had already been started up.

Post release content, in the form of downloadable content (DLC), provides a unique opportunity for game developers. It gives them a chance to increase the scope of the original game, provide additional content for the players, and occasionally the chance to expand upon ideas present in the original game that they felt needed more attention or love. DLC is a chance for developers to listen to their fan base and provide something that caters to their wants and needs or shape how a game is played and supported many months or years after its original debut.

Halo 3 would follow in the footsteps of Halo 2 in terms of post-release support. The Heroic Map Pack was the first batch of new maps for Halo 3’s multiplayer and became the first stepping stone for extending the game’s post-launch success. The smallest of the three included maps was Foundry.

Set up fictionally in an abandoned factory somewhere near Voi, Africa, the level was essentially a large open hall, split between two sides with a few corridors and rooms at the very back. The colour palette consisted of muted greens and browns and it rocked a dull, industrial vibe. Of all of the possible vistas Halo has delivered and the unique alien spaces the game is known for, the map was seemingly dull, lifeless and visually uninspiring.

Foundry was harbouring a secret. The name alluded to the level’s real purpose. This abandoned factory was going to be the workshop in which many players would forge new creations, new levels and new ideas. Foundry was more than a simple map included in a DLC pack; it was the first real expansion to Forge, a lens that would allow players to see the true potential of Halo’s new mode.

I came in with no expectations and only the customization options in Halo 2 to compare it with. It wasn’t until Foundry’s release that I even bothered jumping into Forge. Despite having never tried a map editor I was instantly determined to create something my friends and I would be able to play on, envisioning the canvas as a melting pot in which I could mix pieces of all my favorite maps into one.

And then I tried to use it.EazyB

Soon after the release of the Heroic Map pack, players had begun to scratch at the surface of what was possible. The results were varied and interesting, from simple rearranging of the objects in the level to brand new level layouts as the maps started to flow from Foundry’s Forge.

Whole new gametypes, challenges and ways to play developed in tandem with the explosion of new community created maps. Map designers quickly started to push the boundaries of what was possible with Foundry. Players found clever tricks and glitches to escape the map, merge objects into the level geometry and a host of other ways to bend Forge and the map to suit their needs.

Foundry became the test bed for pushing what was possible in Forge. Through patience and determination players found how to get the most of the Forge even if it meant countless hours spent lining up walls to perfection. Foundry demonstrated that the players were willing to invest in Forge and certainly more than content to reap the rewards.

Grifball, a competitive multiplayer game born in Foundry’s Forge, became the prime example of what was possible. It took elements of Neutral Assault and the fast-paced nature of team sports games and combined them into a new competitive, multiplayer gametype. Aiming and shooting took a back seat as the new gametype emphasised movement and team co-ordination. Not a single shot would be fired, yet the bodies would pile up higher than in any other mode and rounds would end with mayhem framed by an explosive win or loss. It was something new and different, but uniquely Halo. Grifball‘s popularity soared. It featured regularly in weekend Halo 3 playlists and tournaments attracting Halo players from across the internet.

Bungie could have sat back and enjoyed the success of Forge at this moment in time. Players were happy to continue to spend countless hours making new map variants and discovering new glitches to exploit. With the release of the next DLC, the Legendary Map pack, it did seem as if Bungie was happy with this new status quo.

Every level could be changed in Forge to some degree, and Foundry was a box of possibilities, but players had started to come across many limitations with it. Some felt that Foundry was cramped whilst others wanted more objects to build more complicated layouts. Everyone wanted more.

I created a few maps in Foundry but eventually decided there wasn’t much left for me to do within the limitations of that canvas. I now expected to create maps to play… and I just wasn’t quite able to create maps worth playing alongside Bungie’s shipped maps.

EazyB

It’s true that, first and foremost, Bungie makes games they themselves want to play, but as Halo shows we all want to play these games too. It came as no surprise that Bungie was listening to its fans when the DLC started development. Remakes of old fan favourites were included beside new offerings in addition to the playground that Foundry represented.

The Mythic Map pack represents Bungie’s final contribution to Halo 3. Bungie took the opportunity to once again revisit Forge and gave players one final sandbox to play and create in. With Halo: Reach still in its earliest stages of development at the time, it seems as if Bungie just couldn’t wait to see what its fans could do with Forge taken to its limits.

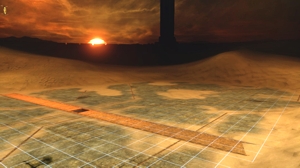

Sandbox. The name of the map is pretty self-explanatory. It was a virtual playground, a field of conflict and an artist’s den all in one. The map was like nothing ever seen in a Halo game; it defied convention as much as it did expectations. It featured three separate planes to create levels – in the sky, on the ground and deep underneath the sands. The sheer scale and size of the level was stunning when first seen and remains so even today. It took the premise of Foundry and ran with it. And kept going.

I didn’t build a serious, from-scratch map until Sandbox hit; my work on Foundry was mostly just messing around with fusion coils.

GhaleonEB

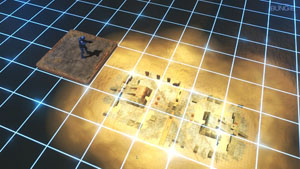

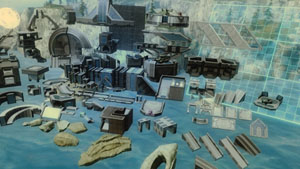

Sandbox empowered the players like no other map before it. The very layout of the map challenged players to come up with new ideas. Across each of the surfaces of Sandbox players would see a blue glowing grid whilst using Forge. This was Bungie helping out the players by assigning a huge grid to the entire layout and facilitating the design of new map layouts. The budget limit for the level was massive and the number of objects the player could use was seemingly endless with various types of walls, slopes, blocks and columns.

Sandbox’s reveal reignited my interest in Forge. It solved the issue that made me stop creating maps, it was bigger – bigger canvas, bigger budget, and bigger object palette. Custom games were frequent and Sandbox map variants were a significant draw.

EazyB

Sandbox was a statement to the fan base, a vote of confidence in their ability to create new, original content and it was clearly designed to help the process along by giving the players more tools and canvas.

Forge’s original restrictions were still in place. Players needed to glitch objects and exploit certain behaviours in order to get what they wanted out of it. This restriction belonged to the game engine and it wasn’t something that could be fixed by a simple DLC download or update. Naturally enough, players worked their way within or around these restrictions with their creations. New maps came out at a faster rate than ever before.

Bungie attempted to channel the output of the community into Halo 3’s matchmaking after the release of Sandbox. Previously Bungie had selected a few community-created maps and integrated them into various playlists. A new attempt was made, using the popularity of Sandbox, to see if a host of new content could make it’s way from the living rooms of the players to the front lines of Xbox Live’s premier multiplayer experience.

ATLAS was a private group set up on Bungie’s forums with the aim of looking at submitted community maps and filtering the best ones through to playtesting and eventually into matchmaking. The results were surprising.

Over Halo 3’s lifetime post release, Bungie’s official maps and its own variants totalled twenty four whilst the number of community variants, largely coming through ATLAS, totalled sixty. A victory for Forge and Sandbox clearly, but not quite so for the community.

My first thought was to recognize the constraints imposed on any such system, beginning with the fact that Halo 3’s Forge was not designed to do what it ended up being used as, a faux map editor. Since that was not part of the initial design spec, Bungie did not have any infrastructure in place to build a pipeline from custom content on through to matchmaking. And because someone from Bungie had to be on the end of the process, they would only ever be able to touch a tiny fraction of community content.

GhaleonEB

As Reach’s development ramped up, the already small resources dedicated to ATLAS dried up. What started as a promising channel for funnelling community content into matchmaking met with only limited success.

Forge reached its full potential with Sandbox. It was far from the path it started out on. No one was flinging tanks at each other in any serious capacity; instead Forge became a tool for creating new play spaces and recreating old favourites.

In the end, Forge went from an object placer to a tool which you could really see almost anything created. The only hard limit was the budget limit, stopping players from getting too ambitious with the size of the maps. You could really contort Forge’s barbaric tools to do almost anything you needed, it just took an unreasonable amount of time and many, understandably, couldn’t put up with it.

EazyB

It revived dead gametypes as well as creating new ones. Forge single handily changed how Halo was played by silently being the glue that held together a larger, more connected community. To some players it was all that and more.

Whilst vehicular destruction and mayhem is one of the Halo series’ most revered hallmarks, competitive multiplayer racing within the Halo series has been largely ignored.

Originally a gametype in Halo: CE, Race allowed players to tear across multiplayer terrain with the goal of beating other players to the next checkpoint and reaching the end destination first. It relegated players with skilful weapon control to the backseat whilst giving drivers their time in the spotlight. It wasn’t popular. Compared to the regular Slayer and Objective games at the time, it’s easy to understand why players would have preferred to polish up their Sniper skills rather than their Warthog handling.

As a further sign of popular opinion, Halo 2 and Halo 3 both shipped without the mode. It seems like Race was going to be a forgotten relic of Halo’s past – until players discovered Forge.

Even though Race was absent from Halo 3, a mode was included that bore certain similarities. Rocket Race was a VIP variant in which two players, the driver and the VIP, competed against other teams of two across the maps to reach various checkpoints that appeared sequentially. Whilst this wasn’t the same as the original gametype, it was enough to give inspiration to the community. The community duly noted the strengths and weaknesses of the new racing variant and went about shaping and perfecting it to suit their own ends.

With Forge and its associated glitches and exploits, players were able to resurrect this game mode by altering, not just the existing VIP gametype, but the levels themselves.

Anyone can place a few checkpoints across the terrain of a level and call it a day, but the Halo community’s bottomless well of creativity ensured that this was just the beginning. With the discovery of geo-merging (the ability to merge an object into the level geometry) and ghost merging (merging objects into anything, including each other), the number of new racing tracks blossomed. Foundry and Sandbox are responsible for an incredible quantity of newly created levels designed exclusively for competitive racing. Players quickly found almost limitless inspiration from the rich palettes both of the levels offered. Objects seamlessly blended and merged with each other and the environment provided smooth roads which would twist and turn into and the skies and back again.

Players fought against Forge’s rigid restrictions and through time, dedication and meticulous attention to detail created some of the most impressive displays of creativity.

Forge was the tool that allowed the community to resurrect a forgotten game mode and push it further than Bungie had ever considered. Hundreds of viable racing tracks now litter players’ Fileshares and Xbox 360 hard drives. From simple point A to point B courses to elaborate multi-lap courses, the community has created a wide variety of assorted courses according to their own wants and designs. It is unlikely that Bungie could have ever expected Forge to be utilised on this scale and in this particular way. The sheer scale and enthusiasm exhibited by the Halo community to pull it off in such a fashion and do it successfully is simply unique to Halo. In no other console game has this been done on this scale and it is a credit as much to the community’s efforts as it is to the developer’s product.

Halo photography and machinima are not by-products of Forge. Photography started out in earnest with Halo: Custom Edition for the PC, as players used various tricks and external programs to get a better look at some of Halo’s beautiful vistas and set pieces. Likewise, Halo’s machinima came about from similar roots. Forge has proved itself to be a powerful and indispensable tool for this section of the community.

Halo 3’s Theatre mode took photography from a niche interest to the largest ever audience. Now every Halo player could be a potential photographer. Where most players would simply capture a few key moments of their own gameplay in Campaign or multiplayer, a more hardcore group of fans would go that extra mile and use the opportunity to further explore the Halo universe and capture and create unique moments unseen by other players.

Photography in Halo can and has existed perfectly well outside of the use of Forge. Forge however brings about additional opportunities and scenarios that wouldn’t be available without it.

With Forge you can relocate specific objects around a level, remove them completely or even add additional objects to a level. Players quickly discovered glitches and tricks using Forge. Objects could be stacked on top of each other and then made to appear as if floating. Certain weapons and equipment had very localised effects which could change the visual appearance of objects and players in a small area. Halo players are some of the most creative folks out there and the photographers are on par with anyone else. Forge was put to the task of creating stages and setups for capturing uniquely Halo moments.

Forge gave the player additional control over the environment and lent itself to empowering the player and broadening the scope of what is possible.

For machinima creators, stages could be built within minutes. From simple object swaps to elaborate set pieces, Forge has the ability to turn players into set designers.

With the launch of the Legendary Map Pack, photographers and machinma directors were gifted with the addition of Forge Filters. These filters added a visual effect to the entire level and provided photographers with yet another element with which they could put to use as they saw fit. Lighting plays an important role in photography and the Halo photographers were quick to utilise the new feature, producing new images that would not have been possible previously.

One of the most unexpected series of products to come from Forge has to be the placement of objects and weapons to be produce “art”. Without wanting to delve into the validity of such creations as a form of art, it’s clear that this Forge offshoot has been developed by talented players.

With the discovery of glitching in Forge, players could merge objects together – a rudimentary form of digital sculpture was born.

What started as technique for aiding in traditional map creation became an outlet itself for some stunning creativity. The map themselves may been dreadful to play in traditional multiplayer but the centre pieces were absolutely stunning.

In the UK for over a decade there has been a children’s art television show called Art Attack. One of the highlights of the show would be the big “Art Attack” art piece created by the presenter – he would gather many household items and take them to a massive natural canvas (such as a field or car park) and place each item in a very specific place. As the feature went on viewers would attempt to guess what was being created before the presenter was finished. When he done, the camera would pan high above the artwork and look down from above and reveal that the assembled household items made up a giant piece of art.

In Forge this is exactly what players have done. Objects are spawned put into place, piece by piece and when the player is finished, he or she would pan out from his creation at just the right angle and a picture would emerge.

You can see stunning examples of this “Art Attack” type art in the Fileshare of thousands of players. Some were original creations whilst others are loving recreations of population cartoon characters or Japanese animation personalities. Community created clans would proudly display their logo and creative individuals could use their Fileshares to make a point.

Unfortunately, there exists a seedier side to this artistic boom within Forge. Like it or not, the ability to “draw” images in Forge would quickly lead to images you wouldn’t see on TV before the watershed.

Inappropriate and offensive images soon flooded all over the online community. Hate images, featuring racism, sectarianism or sexist images and comments also found their way out.

Thankfully common sense prevailed and such material was rightfully prohibited amidst a renewed crackdown and fair wielding of the Banhammer. Whilst Forge could be a canvas for almost unlimited creativity, the Halo community at large and Bungie decided to keep it clean.

The professional videogame league, MLG, has been at the forefront of competitive Halo multiplayer for years and it should come as no surprise that MLG and its followers have embraced Forge.

MLG is well known for having strict, specific setups for its competitive games. The group decides on a certain, specific way to play the game in order to promote its competitive values and make the setup fair, balanced and equal for all of its players and participants.

Forge allowed MLG to redesign the existing multiplayer level’s weapon and feature layouts to meet their own standards and criteria. Certain weapons would be removed from maps; other weapons added in, equipment removed and so on. This, in addition to creating and distributing customised gametype variants, allowed MLG to set its standards for competitive play very quickly and easily. In addition, Forge let MLG quickly revise its chosen setups which has resulted in an evolving set of rules for the MLG players as feedback can be taken into consideration and the maps altered as appropriate.

MLG has also selected custom maps designed exclusively in Forge to appear in its tournaments. MLG’s narrow criteria means that not all available shipping maps would be suitable for MLG style play, as MLG tastes tend to favour the medium and small arena style of play. The ability to create and integrate Forge maps into the MLG circuits has resulted in an increased variety of maps for its followers and players to enjoy.

It should also be noted that the MLG playlist in Halo’s matchmaking is the only permanent playlist consisting solely of Forge and Forged variant maps. This is a great example of how prominent Forge can be in Halo’s matchmaking.

At this year’s Comic-Con Bungie unveiled Halo: Reach’s version of Forge to a crowd of excited Halo fans. They had every right to be excited. Forge 2.0 was unveiled alongside a new multiplayer level. This level would be the spiritual sequel to both Foundry and Sandbox and it is fittingly named Forgeworld. Such a bold name for any level. It must live up to the expectations of loyal players and meet Bungie’s strict criteria for quality.

When Bungie unveiled Forgeworld it did so by bringing back an older, fan-favourite – Blood Gulch, now lovingly recreated within a small sub-section of a larger playground. The enviroment is set on a Halo ring as the huge Forerunner structure can be seen climbing into the heavens from the horizon. The sky is clear, the rolling green hills sit serenely and the ocean quietly laps across the coastlines. Forgeworld sets new standards for scale in a Halo multiplayer level. Originally designed as five seperate levels before being knitted together by the designers and artists into one huge canvas, Forgeworld represents the most ambitious Forge playground to date. It is a confident acceptance of the wants and needs of the community.

Forge 2.0 features almost every item from my wish list including the modern Forerunner architecture. Forge World goes well beyond my expectations.

NOKYARD

Where Sandbox split itself into three distinct areas requiring the player to work within the sectioned areas or attempt to bridge these areas with teleporters or other methods, Forgeworld is a single unified stage. Players are given the freedom to select which area to use and design around and which areas, if any, to keep closed off.

One of the most important improvements to Forge with Halo: Reach is the standardisation of techniques that previously could only be accomplished via glitching the software or by wasting hours attempting to perfect. Forge has incorporated phasing objects with each other and the environment, it has changed how players interact with objects so a single wrong mistake would not irreversibly damage the delicate house of cards. Players now have more control over the basic manipulation of objects so simple tasks such as alignments are now simplified and swift instead of frustrating and time-consuming.

Forge 2.0 is infinitely more accessible than H3’s iteration which will automatically result in more people creating maps. No longer will the quality of the map be based on how well versed you are with the latest glitches and exploits, but a much bigger influence will be on how well designed the user’s creation is.

EazyB

Forge 2.0 contains more building blocks and a higher object budget than any map before it. More objects, more more geometry, more space, more variables and more choice. It has been designed to simplify things. Accomplish the same tasks quicker and easier than ever before. It contains more options, more variables, more choice and yet, somehow, it comes across as a much more approachable and user-friendly tool.

Bungie had the time and resources to overhaul Forge from the ground up and they did just that. It is tailored to the community, tailered to how the community has used it over the years.

As much as any developer I’ve seen, they build content and features that cater directly to what the community wants. Nearly every major – and minor – feature that they’ve added to the series over the years has stemmed from the demands of the community, from map remakes to custom game and map tools to content sharing and the suite of features on bungie.net. Each subsequent games features reads like a wish-list from the previous one.

GhaleonEB

Race makes a triumphant return in Reach thanks to wonderful support the community put behind the mode in Halo 3 even when it wasn’t fully supported. The fans wanted it and with Reach, Bungie delivers. Grifball was created in Forge in Halo 3 and now it too returns as a full mode available in Reach.

Forge has become a medium, a tool for the community to make a point. It is a lens which lets Bungie see how the players want to play their game and a tool that lets players make the game their own. Forge has defied expectations and gone beyond what any reasonable

person could have ever envisioned from it. Forge 2.0 will continue to push these boundaries further even if it remains to be seen if Bungie can utilise the fruits of the community and funnel it through back to the players.

With Forge, the impossible is possible. You can bring back old classics, create elaborate set pieces, design new game experiences or just fling around tanks.

Dani

Article Errata

For the article I was lucky enough to be able to interview three community map makers that have maps currently active in Halo 3’s playlists. These nice folks took the time to answer some questions I put to them and from which I pulled the quotes used in the article.

Forge Q&A: EazyB

Forge Q&A: GhaleonEB

Forge Q&A: NOKYARD

![]()

Nice, especially going into Halo Reach this month with forge.

Ascendant Justice forums maybe nice and all that, but i liked FUD forums… sad they went.

Looking forward to the gallery

Nice article.

Now, where is our FUD Forum? Dani, cant you put it back??? We where building something…. cool themes…all gone? … hope we ca put them back, right beneath Ascendants Forums.

Well written.

I do wonder though, is it possible to create invasion gametypes using forgeworld?

@Andre

this is really late, but yes, bungie posted a tutorial on how to do it a while back, i cant find a link right now but yes, it is possible! =D